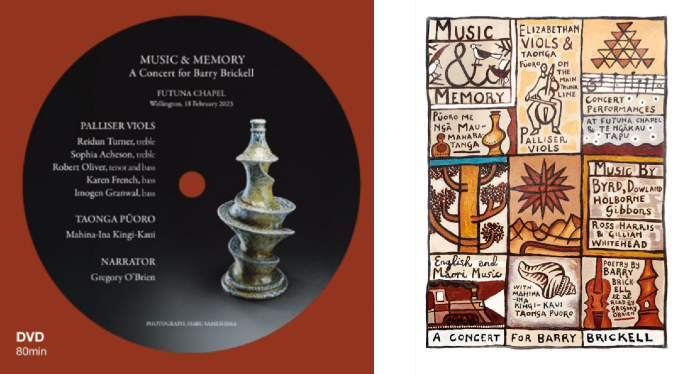

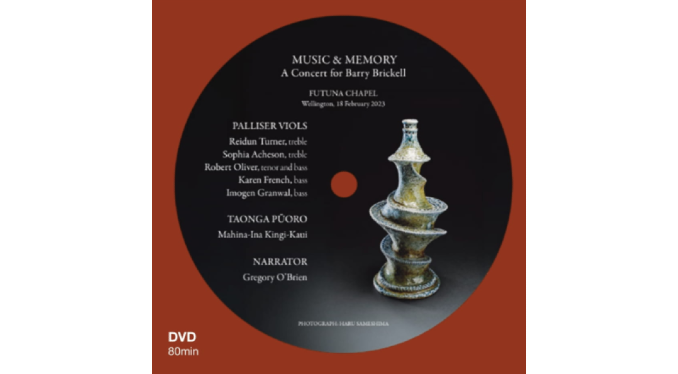

Music & Memory

Music from pre-colonial England and pre-colonial Aotearoa collaborate to produce a new and beautiful harmony.

A magical mixture of sounds, images from colonial New Zealand, European renaissance art, readings from iconic New Zealand potter, sculptor, writer and railway builder, Barry Brickell, a multi-layered unique experience.

Music & Memory performed in Futuna Chapel, Karori, and Te Ngākau Tapu, Porirua in February 2023 is now available as a DVD.

Published together with the sumptuously illustrated, full colour programme booklet, it is a video recording of the entire concert featuring music from pre-colonial Elizabethan England together with music from pre-colonial Aotearoa. It includes music specially composed for the concert by Gillian Whitehead, for taonga pūoro and consort of viols. Other pieces by Gillian, and Ross Harris, combine with music by Byrd, Holborne, Robert Parsons, Orlando Gibbons &c for 5-part consort of viols.The 43 page booklet, which acts as a casing for the DVD, contains the programme and programme notes with many illustrations. These include the 14 tiles of Barry’s ‘Stations’, photos of his pots by Haru Sameshima, of taonga pūoro, together with reproductions of renaissance paintings of viols. It is an integral part of the presentation, and should be read as the DVD is viewed.

“The audience sat thoughtfully at the end of the concert, moved by the richness of the occasion. Oliver’s multi-layered tribute to Brickell is a conception of genius that deserves to be more widely experienced.” — Elizabeth Kerr

The full review can be seen on https://www.fivelines.nz/articles/music-amp-memory-a-tribute-concert-for-barry-brickell

Filmed by Bruce Foster, with Chris Watson of SOUNZ. Recorded by David Muir.Reidun Turner, Sophia Acheson — Treble Viols

Robert Oliver — Tenor and Bass Viols

Karen French, Imogen Granwal — Bass Viols

Mahina-Ina Kingi-Kaui — Taonga Pūoro

Gregory O’Brien — Narrator

Bruce Foster — Producer and Booklet Design

Contact Form

DVD & Booklet — $35 + shipping

DVD Only — $25 + shipping

Also directly available from Robert Oliver:

E-mail: [email protected]

Phone: +64 210 257 4375

Music & Memory is a concert where two ancient traditions, both recently remembered, come together in harmony. With the revival of taonga pūoro, and of the sounds of the consort of viols, this programme of pre-colonial English music combines with the pre-colonial traditions of tangata whenua in a spirit of companionship, rather than competition.Unique in our landscape, our mix of cultures and peoples, and our pride in this mix, this is a singularity we alone possess. The work of Barry Brickell expresses all of this, and the concert is inspired by and dedicated to the ideas he initiated through his pottery, his writings and his railway.

Mahina Ina Kingi Kaui

Taonga Pūoro

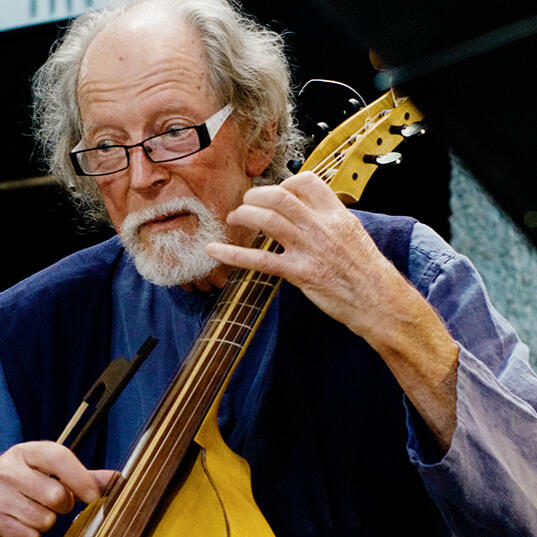

Robert Oliver

Tenor and Bass Viols

Imogen Granwal

Bass Viol

Karen French

Bass Viol

Reidun Turner

Treble Viol

Sophia Acheson

Treble Viol

Gregory O'Brien

Narrator

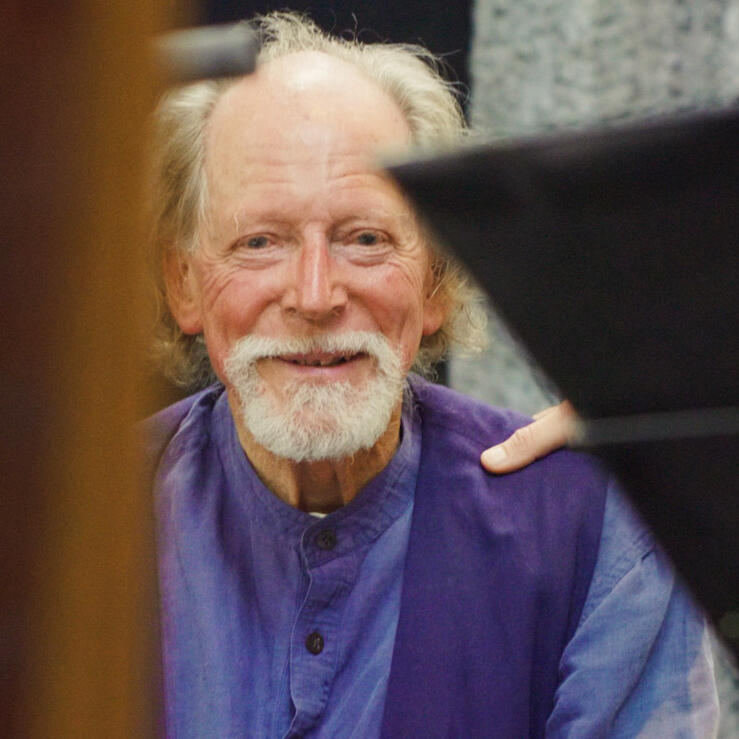

Robert (Relieved)

Memories (a pre-concert talk) by Robert Oliver

I need to explain a few things about this project. It is made up of three elements: the music from the two traditions, the words from Barry Brickell, and the pictures in the programme booklet which illustrate Barry’s art, the instruments, and aspects of our colonial history. You can bring the three elements together by using the booklet as a programme guide, turning the pages as we progress.This project is a very personal one, and tied up with not only my life, but the lives of many of my forebears. It is born out of the issues many of us have grown up with, which have shaped us, and my experience is, I believe, of broad enough interest for me to share some personal details.I grew up at a time when steam engines pulled our trains through our landscape, when we played cowboys and Indians and watched movies about them, when the grocer delivered our week’s supplies, and Māori were among our friends, present in our schools, in our choirs and rugby teams, and the only te reo we ever spoke was the school haka.My connection with the Railways goes back to when I was a boy, and I went to a school far from my home, and I vividly remember standing in the Hastings railway station as the train, drawn by a mighty steam engine, made its huge entrance, steaming, puffing rhythmically, clanking, monstrous and overwhelmingly majestic and beautiful.Then, later in the ‘60’s, sort of grown up now, Andrea and I were married, and I met her brother – Barry Brickell – for the first time in his then house in Coromandel, where he was making a living from pottery, and had built a railway to fetch clay and deliver his pots to the roadside: it had viaducts, cuttings, mostly gone when he sold that house and moved up the road to a larger property where the famous Driving Creek Railway now operates. His enthusiams, his art, and his powerfully articulated vision of what it was to be a New Zealander, not British, not European, not subject to ‘overseas standards,’ but of this place, was electrifying, and infused our life together from then on.This notion of what is unique about ‘our place’ was also a big issue for our great composer, Douglas Lilburn, and he talks about that in his essay ‘A Search for Tradition’ describing a time when he was on the Limited going through National Park: “.. and in the moonlight I could see an uncanny picture of Ngauruhoe and Ruapehu. I was so excited by this as I hung out of the door of the carriage as we came from National Park down to Raurimu at the foot of the spiral. There was something very strange about that experience of speeding through the night with the vivid night smell of the bush country around me. At that moment the world that Mozart lived in seemed about as remote as the moon..” It is to this passage that Gillian Whitehead responded in one of her pieces she wrote for us to play in this concert, expressing the inner conflict through the images of the restlessness of the train and the strangeness and serenity of the moonlit landscape.Why viols? In the ‘60’s, as a student in Wellington, I had encountered Elizabethan song, Dowland, Campion, Pilkington and others, and fallen deeply in love with them, a love for music of that period that since then has never wavered. I also found that the instrumental music of the time called for a string sound not then available. In my early student attempts to conduct small orchestras and choirs, I had asked the string players to play without vibrato – something they were very reluctant to do. When I finally arrived in England, in 1967, I encountered viols, whose beautifully astringent, chystaline sound answered that question. My subsequent musical activity has been shaped by these experiences.So I should talk about viols, as there will be some, I hope, for whom they are a totally new experience. They used to be played in Europe, until the time of Mozart. They were swept away in the revolutionary fervour of that time, associated as they were with aristocrats and privilege. Their music lay silent for 200 years, and their techniques forgotten. Then, just over a century ago, people became interested in them again, and rediscovered their silver sounds and the wonderful music written for them, which can only really be played on them. Since then, lots of people have become familiar with them and their music, not just in Europe, but in America, China, Korea, Japan, and, of course, Australia and New Zealand.In its own time their music was regarded as contemplative music, as one writer of the time put it: ‘We had for our grave music, fancies of 3, 4, 5 and 6 parts, with some pavans, almains, solemn and sweet delightful ayres, rhetorical and sublime discourses, subtle and acute augmentations, so suitable and agreeing to the inward, secret and intellectual faculties of the soul, that they have been to myself and many others, as divine raptures, powerfully captivating all our unruly faculties and affectations, and disposing us to solidity, gravity, and a good temper, making us capable of heavenly and divine influences.’Similarly, taonga pūoro were swept aside by our colonial forefathers, similarly they were almost, but not quite forgotten. Further they performed a significant solemn and spiritual function in the important moments of daily life in te ao Māori. So it is appropriate to bring them together with viols in a new harmony. In her 2019 Lilburn lecture, Gillian Whitehead relates the story that Lilburn wept when he first heard taonga pūoro, saying that he had waited all his life to hear those sounds.That should partly explain this curious, personal and multi-layered assembly of music, poetic musings, and railways. But there is more. My grandmother’s uncle, Charles Wilson Hursthouse, was the surveyor who plotted the route of the Main Trunk Line through Te Nehenehenui – the great forest of the King Country. Before that he had been the surveyor who put in the pegs that Te Whiti and his followers pulled out. Fluent in te reo, he had been the translator for John Bryce, in the government’s discussions with Te Whiti. He was also a member of the Taranaki volunteer militia, and, with his Richmond and Atkinson cousins, fought in the Land Wars.Based in New Plymouth, he spent some time in Te Kuiti, and while there, formed a relationship with Mere te Rongopamamao, and the daughter of that relationship, Rangimarie Hursthouse, married Tuheka Taonui Hetet, and as Rangimarie Hetet, became famous as the reviver of the techniques of traditional weaving. She also had a large family in the Waikato, several of whom I met when I was setting up the 15-concert tour that this was supposed to be.So, like many people whose forebears came from Britain in those early years, I sit uncomfortably right in the middle of what we now acknowledge to be a very complex and multi-layered series of issues. The questions that now sit before us, with our present knowledge, have to find answers. We need to be led by someone like Barry Brickell, who found his own pathway through his art and his intense identification with ‘our place’. Our memories raise many questions, to which we must find a creative and beautiful response.And hopefully all of us long to find answers that are positive, creative and just. This assembly of music, pictures and words, is a response. It best be described by an American poet, also a country where similar issues have found answers which raise yet more questions. She is Mary Oliver – no relation as far as I know – it’s a brief aphorism:The man who has many answers

Is often found

In the theaters of information

Where he offers, graciously,

His deep findings.While the man who has only questions,

To comfort himself, makes music.